Having established the team we now know as West Surrey Racing via fax in January 1981, New Zealander Dick Bennetts – already owner of a sizeable reputation for racing car preparation – was on a mission.

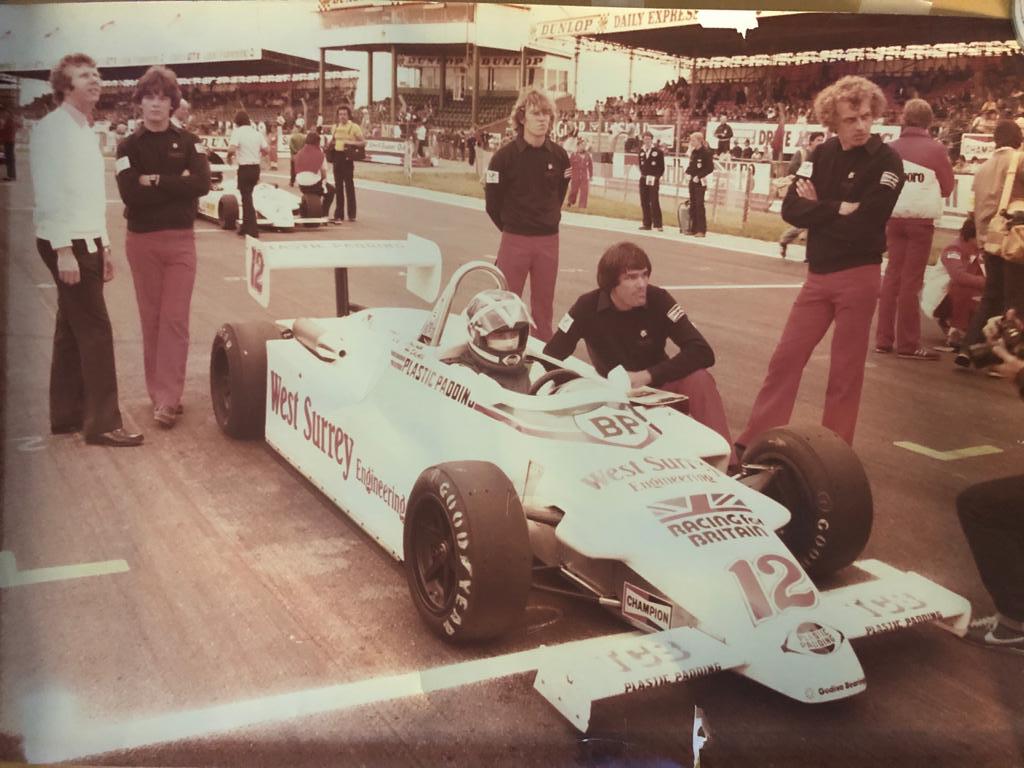

With a crack team of, erm, three-and-a-half, Dick and the boys were ready to take on the world in the intense world of Formula 3 with driver Jonathan Palmer – protégé of West Surrey Engineering owner Mike Cox.

“It was a bit of a departure from Project 4,” recalls Dick, who had engineered Stefan Johansson to the previous year’s title for Ron Dennis’ team, which had, during the winter, left the category and taken over McLaren’s F1 operation.

“We’d had 14 full-time staff there, and now there was just me, Harvey Spencer, Dave Stephens and Jamie Palmer – Jonathan’s brother – who joined us at weekends.

“I was pretty pleased to realise quite quickly that Jonathan was – as well as being fast – very intelligent with his feedback and intensely committed to his racing.

“He was still doing his doctor training at this point and he’d regularly finish a long shift in the hospital and then drive straight to a track for a test. Sometimes we’d arrive about 8am and find him fast asleep in his Golf GTi!

“You always knew a guy like that would make it, so it’s been no surprise to see the success he’s had as a driver and a businessman since [Palmer is now head of MotorSport Vision, the UK’s largest operator of race circuits].

“We did what testing we could and seemed to be in decent shape. Of course, you never really know where you are until you get on-track with everyone else for the first event…”

That first event came at Silverstone on March 1, 1981. Palmer put the Ralt on pole position and won the race.

It was remarkable debut for team and driver by anybody’s standards, but against a top-quality field that included Raul Boesel, Michael Bleekemolen, Thierry Tassin, James Weaver, Toshio Suzuki, Kurt Thiim and David Leslie, it was nothing short of astonishing.

It didn’t stop there either…

“We won the first four races,” Dick explains. “That was massively beyond expectations. We did it without a spare engine too – Mike Cox’s attitude was that we didn’t need one because we were winning. That was a hard argument to win, but he did what was needed.”

A strong mid-season run put Palmer in a good position to wrap up the title before the final round.

Then, a problem…

A jealous rival had questioned the legality of Palmer’s Ralt; specifically around its rear bodywork.

“Suddenly the scrutineers paid a lot of attention to a part of the car they’d ignored all year. Someone must have tipped them off,” says Dick.

“We’d put two plastic strips by the rear driveshafts. An F1 friend said it had worked for them in the windtunnel so we did it too. Really it was just to out-psyche the others.

“I was tapped on the shoulder just after the start of the race at Silverstone well into the year and told ‘you could be in trouble later.’ Something was up and the officials were all over the rear of the car afterwards.

“It was very frustrating because they could have pointed it out at the start of the weekend and we’d have removed it. Instead, it turned into a big fiasco.”

Palmer was excluded and stripped of two further wins – as per Motor Sport Association rules. But Dick had an ace up his sleeve as lawyer Ian Titchmarsh – better known as one of the UK’s leading circuit commentators for decades – came to the rescue.

‘Titch’ successfully managed to annul the two additional exclusions (though the Silverstone disqualification stood); the extra points gained back ensuring Palmer was crowned champion officially from Tassin – a major relief and a deserved reward.

Looking back, Dick says: “It’s the only time we’ve ever won a championship on the track and then had to re-win it in the appeal court!”

The car in question; Ralt RT3/80 chassis #198, is rather special. It was bought by Ron Dennis direct from Ralt in mid-1980 and entrusted to Dick, who helped Stefan Johansson to that year’s title with an astonishing four wins from four to round out the season.

Sold to Mike Cox at the end of the year, who later brought Dick in to mastermind Palmer’s season, the car was already an 11-time race winner when Quique Mansilla used it for the first third of 1982 and was sold to privateer Gerry Amato later on.

Purchased many years later by John Cavill – one of Palmer’s backers in ’81 – it made its way into its former driver’s hands, who gave WSR the responsibility of restoring it to full working order; a task chief mechanic Steve Buckell gleefully accepted in 2005.

“We found it in a hangar up at Bedford Autodrome [a facility owned by Palmer’s MSV circuit operations group] and JP asked us to restore it, so we did. It sits proudly in our trophy room,” Dick says.

“It’s in our trophy room now at WSR so we can show our first car to visitors and then lead them into the workshop where our BMW BTCC cars are prepared. It’s a nice touch.

“We had the engine rebuilt and it’s in period spec except for a couple of bits to make it eligible to race in historic events now, like the seatbelts, fire extinguisher, fuel cell and gearbox casing. Steve and the guys who worked on it did a first-class job.”

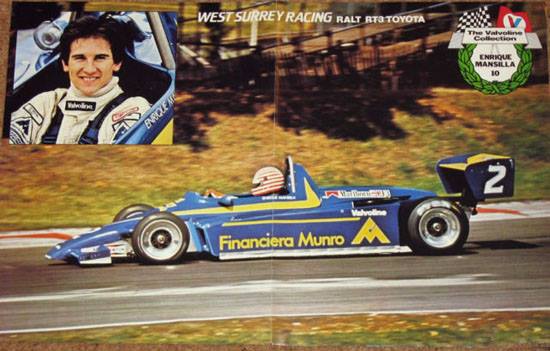

But back to the winter of 1981 and the garage (a glorified shed) that housed the Ralt between races… Palmer, having taken the title, graduated to F2, at which point young Argentinian Enrique Mansilla arrived.

‘Quique’ was introduced to Dick by Autosport’s Stuart Dent and quickly concluded a deal to drive for WSR – the R standing for ‘Racing’, which replaced ‘Engineering’ in the team name around this time. Dick takes up the story…

“Mike Cox had supported JP in F3 so our racing now had to finance the team. He suggested ‘Dick Bennetts Racing’ for a name, but that just wasn’t me.

“I wasn’t a face like Eddie Jordan, Dave Price or Murray Taylor, and was happy to let the results on-track do the talking for the whole team and everyone in it. People knew us as ‘West Surrey’ so we became ‘West Surrey Racing’.

Speaking of the name, it might seem odd that a team that’s never actually been based in the west of Surrey should be called West Surrey Racing. There is, however, a very simple explanation.

“Mike had been part of the West Surrey Squash Club for many years,” explains Dick. “So when he decided to start his engineering business, he was convinced by his friends in the bar one night that it should be called West Surrey Engineering – even though it was based in Middlesex! And that was that.”

The 1982 season couldn’t have started in worse fashion. Mansilla’s ultra-shiny, brand-new Ralt, after an early morning photoshoot (below), managed just 27 miles of testing at Goodwood before it was seriously damaged in a high-speed accident at the final corner.

That necessitated a lengthy rebuild and a switch back to Palmer’s ’81 machine – with which the opening two tests had been conducted – for the first six races.

“That was a real struggle,” says Quique, who now runs both his own PMO Racing touring car team in Argentina and is also head of the domestic Porsche GT4 Championship.

“I’d come straight up from Formula Ford 1600 and wasn’t experienced enough for F3. I should have done FF2000, but my sponsors weren’t interested – they would only support me in F3.

“I always had bad oversteer, and that’s what I kept telling Dick. He kept changing the car to help me, but it never worked. I remember very well at Oulton Park he came out to watch me. When I came back to the pits he said ‘you’re not oversteering, you’re understeering!’”

“I didn’t understand at first, but he explained I was trying so hard to correct the understeer that I was making the rear slide. I couldn’t feel it because I didn’t know what I was looking for – I had no experience of slicks and wings.

“He made some big changes to the car, I went out and was immediately faster. That was a big breakthrough. It transformed the season.”

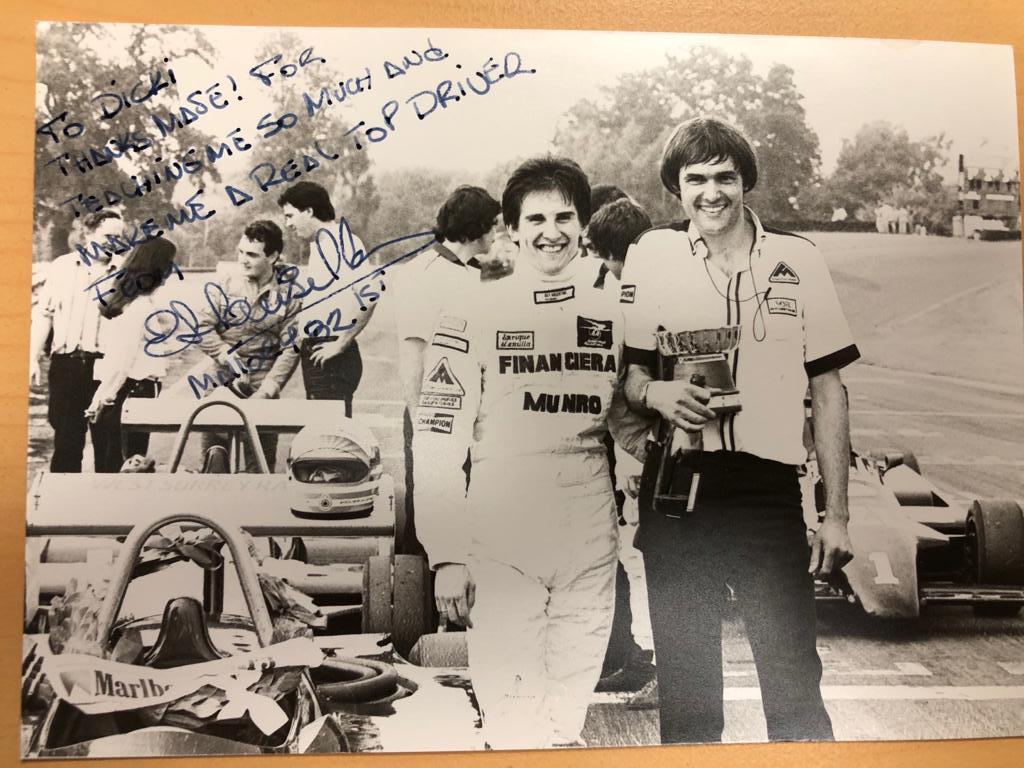

Third place at Mallory Park validated the changes. Second at Snetterton from the front row and third in a European Championship round at Silverstone followed. Then, on June 13, back at Silverstone and now ensconced in his rebuilt 1982 car, he claimed his first win.

Had a rather special visitor a little earlier in the year been an inspiration?

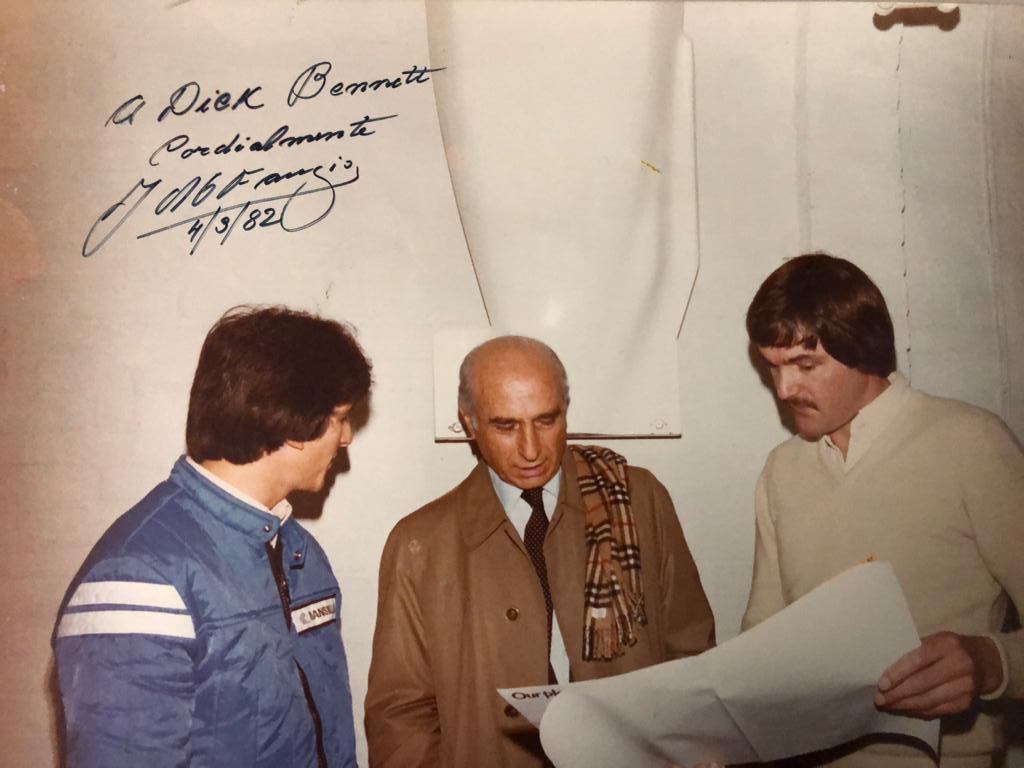

“How could it not be?” asks Quique. “As an Argentinian racing driver, there was nobody bigger in my world than Juan Manuel Fangio.”

“He helped me to connect with some sponsors and when he was on his way to do something in the Middle East, he flew via London and came to see us at WSR. A huge honour.”

Dick remembers the experience vividly: “He was a quiet man – his English was about as good as my Spanish! But he had an aura – exactly what everyone said about him. You knew you were in the presence of greatness”.

“It was only as he was about to leave when Malcolm (Farmer – who worked at WSE and helped us with our paperwork) said we should take a few photos, and I’m so glad he did because it’s a privilege to have the pictures.”

Spurred on by this meeting – and the breakthrough win – WSR’s season went from strength to strength with Quique victorious at Mallory Park, Oulton Park, Silverstone and Snetterton and moving into the series lead.

“Of course, around about this time, the Falklands War began and suddenly Quique’s sponsor payments from Financiera Munro just stopped,” Dick remembers. “We were in a strong points position but had no idea if we could finish the season.

“Mike Cox was fantastically supportive at this point and helped us as much as he could, but we were still on the back foot.”

Quique adds: “We wouldn’t know if we were going to a track until the Thursday before the race. We had to use old tyres for some races too because we couldn’t afford new ones.

“There was one race at Silverstone where I led 18 and a half laps and then went back to seventh in the last lap and a half because the tyres were gone. [Roberto] Moreno tried a move that lost me a lot.

“Without the budget issues, we’d have won the championship. I’m certain of that.”

Quique reached the season finale tied on points with Irishman Tommy Byrne. While the weekend produced a strong third-place finish, there was no repeat-title success. There were lessons to be learnt.

“It was my fault we lost,” Dick says. “We tested at Snetterton with different settings on the Toyota engine and it gained us a couple of tenths there, so we made the call to leave those settings on.

“What we hadn’t factored in was that the loading was greater and for significantly longer at Thruxton, and the engine couldn’t take it any more in that configuration. The head gasket blew in qualifying, so we had to swap engines before the race.”

A replacement powerplant was fitted to the Ralt, Quique came home third, right behind Byrne, who claimed the title by a point.

“It’s always disappointing to lose a championship when you come into the last round leading, but I’d been in racing long enough to know there’d be another year.

Even worse, Dick broke his ankle when borrowing a engine winch crane from Neil Trundle – “I looked like an idiot hobbling around using an umbrella for a makeshift walking stick. My ankle was the size of a football!”

Quique’s career took him to F2, Indycar and – in a bizarre twist – five months as a hostage during a Liberian Civil War after he was captured while working as a gold and diamond hunter in the country.

Now, at 63, his relationship with WSR remains as strong as ever; a point proven last year when son Dorian spent a few months lodging with Dick while contesting the Porsche Carrera Cup GB.

Back to 1982 and Dick was already focused on the next step…

“We were approached by Dennis Rushen about running a young Brazilian called Ayrton Senna da Silva, who was doing very well in Formula Ford 2000,” he recalls.

“Ayrton had huge self-belief and said that if Quique could finish second with us, then he could be champion. We got him in that car for the non-points race at Thruxton, he blew everyone away and the rest is history…”

…History we’ll reflect on in full later this month when we detail the 1983 season with some of the folks at the heart of the action.

Photos: Dick Bennetts private collection, Jakob Ebrey Photography